Cartilage vs Bone: What Makes Shark Skeletons Unique

Sharks are often imagined as muscular, hard-bodied predators, yet beneath that powerful exterior lies an unexpected fact: they do not have a bony skeleton.

Instead, sharks possess a cartilaginous skeleton, a trait that distinguishes them from most vertebrates.

Understanding this difference requires examining the structural and functional distinctions between bone and cartilage and exploring how shark skeletons have evolved to meet the demands of life as apex predators.

Bone vs Cartilage: Structural Basics

In vertebrates such as mammals, birds, and bony fishes, the skeleton is composed primarily of bone — a rigid, mineralized tissue consisting of osteocytes embedded in a collagen matrix, reinforced with hydroxyapatite. Bones are vascularized, allowing growth, repair, and remodeling. Its architecture, with dense outer cortical bone and inner trabecular bone, supports heavy loads, protects organs, and enables efficient locomotion.

By contrast, cartilage is a softer connective tissue, composed mainly of chondrocytes within a collagen-rich extracellular matrix containing proteoglycans and water. Cartilage is typically avascular, receiving nutrients via diffusion, which limits its capacity for repair. In most vertebrates, cartilage is found in non-load-bearing regions, such as joints, ears, and respiratory structures.

The Cartilaginous Skeleton of Sharks

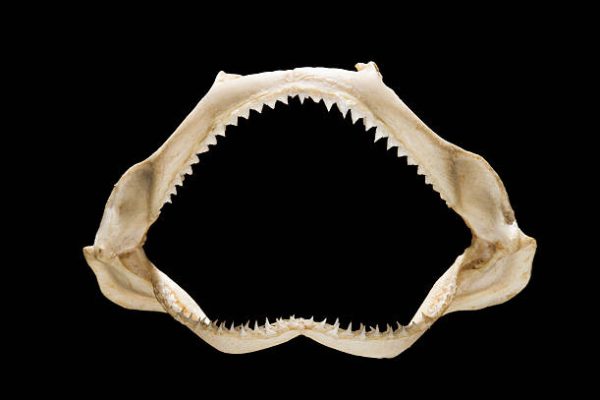

Sharks (class Chondrichthyes) and their relatives, rays and skates, have skeletons made almost entirely of cartilage. Their skull (chondrocranium), jaws, vertebral column, and fin supports are all cartilaginous; the only truly hard structures are their teeth, composed of enamel and dentin.

Despite being lighter than bone, shark cartilage is strong and resilient. Specialized features include:

- Tessellated cartilage: Small, mineralized tiles called tesserae reinforce cartilage in load-bearing areas such as jaws and vertebrae. These tesserae interconnect via collagen fibers, forming a mosaic that increases stiffness while preserving flexibility.

- Calcified cartilage in vertebrae: Certain regions develop dense calcified cartilage analogous to trabecular bone, sufficient to resist bending and compression during swimming and feeding.

This structure enables sharks to withstand mechanical stresses comparable to those experienced by bony vertebrates, making their skeletons far from fragile.

Functional Advantages

The cartilaginous skeleton provides several evolutionary advantages:

- Lower density and buoyancy: Cartilage is about half as dense as bone, reducing overall body weight and helping sharks maintain buoyancy without a swim bladder.

- Energy-efficient swimming: Reduced skeletal mass decreases energy expenditure, allowing sharks to swim long distances or execute rapid bursts of speed.

- Flexibility and maneuverability: Cartilage allows sharks to make tight turns and rapid directional changes. Protractible jaws, enabled by cartilaginous flexibility, allow sharks to project their jaws forward when biting, improving prey capture efficiency.

Evolutionary Perspective

For decades, scientists considered cartilage to be a primitive feature. However, fossils of Early Devonian placoderm-like fish, such as Minjinia turgenensis, reveal extensive endochondral bone, suggesting that bone may have evolved before the divergence of sharks and bony fishes.

This implies that sharks’ cartilaginous skeletons may represent a secondary loss of bone, rather than a primitive condition. By evolving a lightweight, flexible skeleton, sharks gained advantages in buoyancy, energy efficiency, and maneuverability — traits critical for apex predators.

Mechanical Insights

Recent studies using synchrotron imaging and microstructural analysis show that shark tessellated cartilage acts as a composite biomaterial: a soft, uncalcified core reinforced by mineralized tiles. This configuration allows the skeleton to absorb stress, flex under load, and store energy during swimming. Under repeated mechanical testing, fractures remain localized, demonstrating remarkable durability despite the absence of traditional bone.

Conclusion

Shark skeletons are a remarkable example of evolutionary optimization. While lacking bone, their tessellated, partially mineralized cartilage provides strength, flexibility, and reduced density, supporting their roles as agile, efficient predators. Fossil evidence suggests that this skeletal strategy is not primitive but a derived adaptation, finely tuned over hundreds of millions of years to balance strength, buoyancy, and maneuverability.

For sharks, cartilage is not a limitation but a sophisticated evolutionary solution — an internal framework perfectly adapted for speed, stealth, and predatory dominance in the oceans.