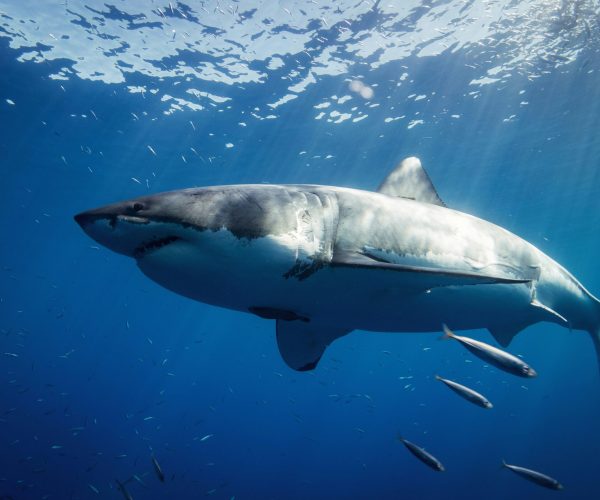

7 Facts About Great White Sharks You Didn’t Know

The Great White Shark (Carcharodon carcharias) is widely recognised as the ocean’s most formidable predator.

But along the South African coast, these sharks exhibit behaviors, vulnerabilities, and ecological patterns that may surprise even seasoned shark‑enthusiasts.

Here are seven scientifically grounded facts about great whites in South Africa — interesting, little known, and critically important. Check out our shark cage diving in Cape Town to see these sharks in person.

1. South Africa’s Great Whites Have Surprisingly Low Genetic Diversity

Recent genetic studies reveal that great white sharks off the South African coast possess the lowest genetic diversity of any known white shark population worldwide. Many individuals share identical mitochondrial lineages — a pattern suggesting a severe historic population bottleneck or long‑term genetic isolation.

This genetic uniformity reduces the population’s resilience to environmental change, disease, or sudden mortality events, making conservation efforts even more urgent.

2. Habitat and Distribution Are Rapidly Shifting

Historically, areas like False Bay and Gansbaai — near Cape Town — were regarded as “white shark capitals.” But a recent regional trend assessment indicates a shift in distribution eastwards.

While some local aggregations have sharply declined, other areas, particularly along the Eastern Cape, now record more frequent sightings and human–shark encounters.

Thus, a stable national population may mask significant local declines and redistributions, complicating conservation and management efforts.

3. Seasonal Patterns & Sexual Segregation in Habitats

A study from 2009–2013 in Mossel Bay documented 3,064 individual great white sightings from youth to sub‑adult stages.

The study found strong seasonal and sexual segregation: juveniles dominated sightings year-round; females outnumbered males overall; and sharks were most abundant during the cooler winter season.

This suggests great whites in South Africa may use sites like Mossel Bay as “nursery or training zones,” where younger sharks learn hunting behaviors before dispersing — adding nuance to our understanding of their life cycle.

4. They Are Capable of Prey Discrimination

Between 2008‑2013, researchers observed 250 individual white sharks at Dyer Island (near Gansbaai), recording over 240 interactions with bait and a seal-shaped decoy.

Interestingly, many sharks ignored tuna bait and approached the seal decoy more often — indicating a clear preference for energetically rich prey (marine mammals).

This “bait‑attracted but prey‑discriminating” behavior reveals that white sharks can distinguish between prey types and may intentionally select high‑energy targets.

5. Population May Be Far Smaller Than Often Assumed

A landmark study by researchers at Stellenbosch University estimated the number of adult great whites in South Africa at just 353–522 individuals.

Given the species’ low reproductive rate and slow maturity, this small effective population size raises concerns about long-term viability — especially under continued human pressures.

6. Many Tagged Sharks Have “Disappeared” — Possible Mass Mortality or Emigration

A sobering 2024 report from the Oceans Research Institute revealed that 18 out of 21 great whites tagged since 2019 in Mossel Bay vanished within four years, despite long‑duration transmitters.

Moreover, mature sharks over 4 m — the important breeding individuals — are now rarely witnessed. Alongside the low genetic diversity, this suggests the population may be in serious decline or undergoing substantial redistribution — a stark warning for conservation.

7. Great Whites Are Under Pressure from Both Human Activities and Environmental Change

Despite protected status in South Africa since 1991, great whites continue to suffer from lethal bycatch in shark nets and drumlines, pollution, habitat degradation, and prey depletion.

Between 1978 and 2018, documented fishing-related mortality included over 1,300 white sharks — most dying after capture.

These pressures — combined with environmental stressors and demographic vulnerabilities — put the long-term survival of South Africa’s great white population at risk.