The Ocean Giants: Types of Sharks in Cape Town

Cape Town sits where the cold Benguela and warmer Agulhas currents meet — a dynamic oceanographic playground that supports surprising shark diversity. Understanding the region’s shark species matters for tourism, fisheries, and conservation alike.

Below is a concise guide to the ocean giants you’re most likely to encounter locally, with peer-reviewed evidence and local research highlighted.

Great white shark (Carcharodon carcharias)

The iconic “air-jaws” breaching behaviour historically seen around Seal Island made Cape Town famous.

Great whites usually concentrate where Cape fur seals aggregate, but their presence has proven temporally variable: long-term monitoring shows sharp regional changes in abundance and offshore movements — including transoceanic dispersal documented from tagged animals — with implications for both tourism and ecosystem dynamics.

Recent tagging and survey studies emphasize connectivity between South African hotspots and broader ocean basins. publih.csiro.au

Sevengill and broadnose sevengill sharks (Notorynchus and Heptanchopterus spp.)

Sevengill sharks, often associated with kelp beds and shallow bays, can increase in visibility where apex predators decline.

Studies from False Bay show behavioral and spatial shifts in these meso-predators linked to white shark absence, highlighting cascading ecological effects when apex predators fluctuate.

These shifts can alter local prey communities and the broader food web. Frontiers

Ragged-tooth / Spotted ragged-tooth (Carcharias taurus)

Although globally threatened, South Africa may host relatively stable ragged-tooth populations in restricted coastal areas.

Peer-reviewed assessments report seasonal and spatial aggregation patterns along the southern and eastern coasts, and recent studies continue to refine our understanding of their reproductive migrations and local hotspots.

Conservation management in Cape waters needs to account for these predictable aggregations. PC+1

Bronze whaler / Copper shark (Carcharhinus brachyurus)

A warm-temperate requiem shark common inshore and offshore around the Cape, bronze whalers are both ecologically important and commercially exploited.

Movement ecology research demonstrates seasonal migrations and connectivity between South African and Namibian waters; bioaccumulation studies also flag potential human-health concerns from consuming shark meat, stressing the need for responsible fisheries and monitoring. ResearchGate+1

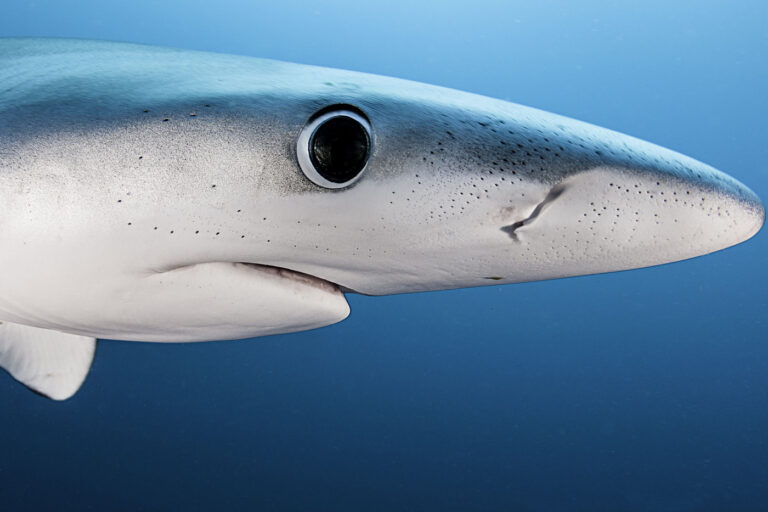

Shortfin mako and pelagic species (Isurus, Lamna, Prionace)

Open-ocean hunters such as shortfin mako and blue sharks visit Cape waters seasonally. Catch data and fisheries indicate these species are vulnerable to bycatch and targeted capture, with international conservation interest because of their slow growth and late maturity.

Regional cooperation is necessary to manage migratory Pelagics that cross jurisdictional boundaries. National Inquiry Services Centre+1

Why Cape Town matters: locally and globally

Local monitoring programs — notably Shark Spotters — combine applied research, citizen science and public safety, demonstrating measurable reductions in human-shark overlap through observation-led beach management (a model for balancing conservation with coastal use). Their long-term sighting databases feed scientific analysis and inform adaptive management. PLOS+1

Management implications and takeaways

- Connectivity: Many Cape sharks are highly mobile; conservation must link local protection with regional fisheries policy. publish.csiro.au

- Ecosystem role: Apex sharks regulate prey and can trigger trophic cascades—losses reverberate through bays like False Bay. Frontiers

- Human interface: Evidence-based programs (spotting, regulated cage-diving, fisheries control) reduce conflict while supporting science and eco-tourism. PLOS

For Cape Town, the science is clear: these sharks are not just icons — they are mobile, ecologically potent species whose management requires rigorous, peer-reviewed science combined with local monitoring and cross-border cooperation.

If you’re diving, fishing, or running coastal policy, grounding decisions in the latest tagging, population and ecosystem research will yield better outcomes for people and for the ocean giants that patrol our shores.